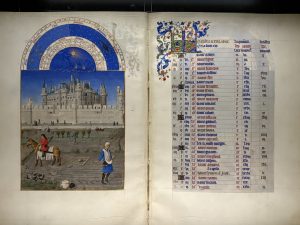

The Très Riches Heures of the Duc de Berry are lavish in the extreme, written in a precise and regular Gothic Textura, accompanied by exquisite paintings by the three Van Lymborch Brothers. There’s more on the Duc de Berry in a previous blogpost here. Each month of the year shows a calendar of saints’ days, feast and holy days, with a Labour of the Month opposite. October is the month for preparing the soil, breaking it down to fine tilth by harrowing, and sowing seeds before winter sets in.

The Très Riches Heures of the Duc de Berry are lavish in the extreme, written in a precise and regular Gothic Textura, accompanied by exquisite paintings by the three Van Lymborch Brothers. There’s more on the Duc de Berry in a previous blogpost here. Each month of the year shows a calendar of saints’ days, feast and holy days, with a Labour of the Month opposite. October is the month for preparing the soil, breaking it down to fine tilth by harrowing, and sowing seeds before winter sets in.

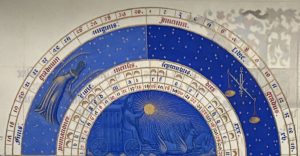

Atop each calendar page is a semi-circular painting of the sky at that time of year with the star sign of Libra giving way to that of Scorpio. In the inner part of the hemisphere is the relentless passage of the sun, drawn by in this case wingèd horses rather than a wingèd chariot. The subtleties in shades of ultramarine blue to depict this scene really are incredible.

Atop each calendar page is a semi-circular painting of the sky at that time of year with the star sign of Libra giving way to that of Scorpio. In the inner part of the hemisphere is the relentless passage of the sun, drawn by in this case wingèd horses rather than a wingèd chariot. The subtleties in shades of ultramarine blue to depict this scene really are incredible.

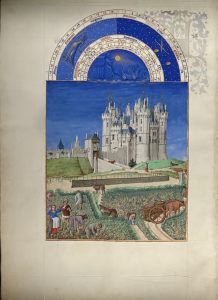

In many of the Van Lymborch paintings the palaces, castles and châteaux of the Duc de Berry are included, and this calendar page is no exception; this time it’s the Palais de Louvre in Paris. This is a magnificent building having a high surrounding wall with round towers, boxy projections over the wall, and battlements with arrow slits. The palace itself inside the wall is huge, as would be expected, with again round towers and battlements, cone-shaped roofs and many chimneys.

In many of the Van Lymborch paintings the palaces, castles and châteaux of the Duc de Berry are included, and this calendar page is no exception; this time it’s the Palais de Louvre in Paris. This is a magnificent building having a high surrounding wall with round towers, boxy projections over the wall, and battlements with arrow slits. The palace itself inside the wall is huge, as would be expected, with again round towers and battlements, cone-shaped roofs and many chimneys.

In the foreground a man with a black head covering, dressed in what looks like an expensive red tunic with a black pouch attached to a belt around his waist, rides a horse with a rather impractical white saddle cloth – in fact the whole ensemble looks more appropriate for a courtier than a man working the soil. The horse is pulling a harrow, a wooden frame with spikes underneath, to break up the lumps in the soil, remove weeds and create a suitable seedbed. Note the scarecrow behind holding a bow and arrow. It doesn’t seem to be that effective with all the birds around. There are even white strings stretched out over that far bed to try to keep birds off the seeds.

In the foreground a man with a black head covering, dressed in what looks like an expensive red tunic with a black pouch attached to a belt around his waist, rides a horse with a rather impractical white saddle cloth – in fact the whole ensemble looks more appropriate for a courtier than a man working the soil. The horse is pulling a harrow, a wooden frame with spikes underneath, to break up the lumps in the soil, remove weeds and create a suitable seedbed. Note the scarecrow behind holding a bow and arrow. It doesn’t seem to be that effective with all the birds around. There are even white strings stretched out over that far bed to try to keep birds off the seeds.

The painting of the harrow is particularly detailed with the struts of the wooden frame and the spikes going in to the ground clear even at this tiny scale. A heavy stone balanced on the harrow ensures that it doesn’t just bounce along on the surface. Magpies and crows are nearby ready to peck at any worms disturbed by the process, and the Van Lymborch Brothers in their usual ‘earthy’ way even include yellow horse droppings in this painting. Note the number of tiny brush strokes with various colours of brown and some white which give such a good effect in depicting the soil.

The painting of the harrow is particularly detailed with the struts of the wooden frame and the spikes going in to the ground clear even at this tiny scale. A heavy stone balanced on the harrow ensures that it doesn’t just bounce along on the surface. Magpies and crows are nearby ready to peck at any worms disturbed by the process, and the Van Lymborch Brothers in their usual ‘earthy’ way even include yellow horse droppings in this painting. Note the number of tiny brush strokes with various colours of brown and some white which give such a good effect in depicting the soil.

The man sowing the seeds also wears a brightly coloured tunic, this time in blue, with his pouch at his waist just below the white ‘apron’ arrangement which holds the seeds being scattered by his right hand. The pouch itself is intriguing; it looks as if it is expandable with a ‘concertina’ of pink leather or fabric between the two black covers, the visible top one being decorated. Two straps, one with a buckle, hang down from the wider side of the pouch and would be used to close it when there is less inside. His expression is not a happy one, and this may be because he is cold – look at the holes in his stockings and the way in which they are frayed at the bottom – or he may just be fed up that the seed he’s sowing is being eaten so quickly by the birds. The detail in such a small figure is simply amazing!

The man sowing the seeds also wears a brightly coloured tunic, this time in blue, with his pouch at his waist just below the white ‘apron’ arrangement which holds the seeds being scattered by his right hand. The pouch itself is intriguing; it looks as if it is expandable with a ‘concertina’ of pink leather or fabric between the two black covers, the visible top one being decorated. Two straps, one with a buckle, hang down from the wider side of the pouch and would be used to close it when there is less inside. His expression is not a happy one, and this may be because he is cold – look at the holes in his stockings and the way in which they are frayed at the bottom – or he may just be fed up that the seed he’s sowing is being eaten so quickly by the birds. The detail in such a small figure is simply amazing!

Yet again the Van Lymborch Brothers have excelled themselves in terms of exquisite and supreme craftsmanship, attention to detail and recording farming activities for the month.

Yet again the Van Lymborch Brothers have excelled themselves in terms of exquisite and supreme craftsmanship, attention to detail and recording farming activities for the month.

There are other blogposts on the months in the Très Riches Heures: July here, August here, and September here.